I often wonder what people mean when they say Kassel has changed over these past two years, during what has been called the “refugee crisis.” Has the city become more diverse? Are social and cultural borders shifting? Such as the border demarcated by Kurt-Schumacher-Strasse, between Mitte and Nordstadt, the home of Turkish, Ethiopian, Bulgarian, and other immigrant communities that arrived in Kassel in the 1960s and ’70s. Or is the change marked by fear, those appeals to the populist imagination that produce profound anxiety around the arrival of new communities, represented through the extreme right-wing sentiments of movements such as Alternative für Deutschland (AfD)?

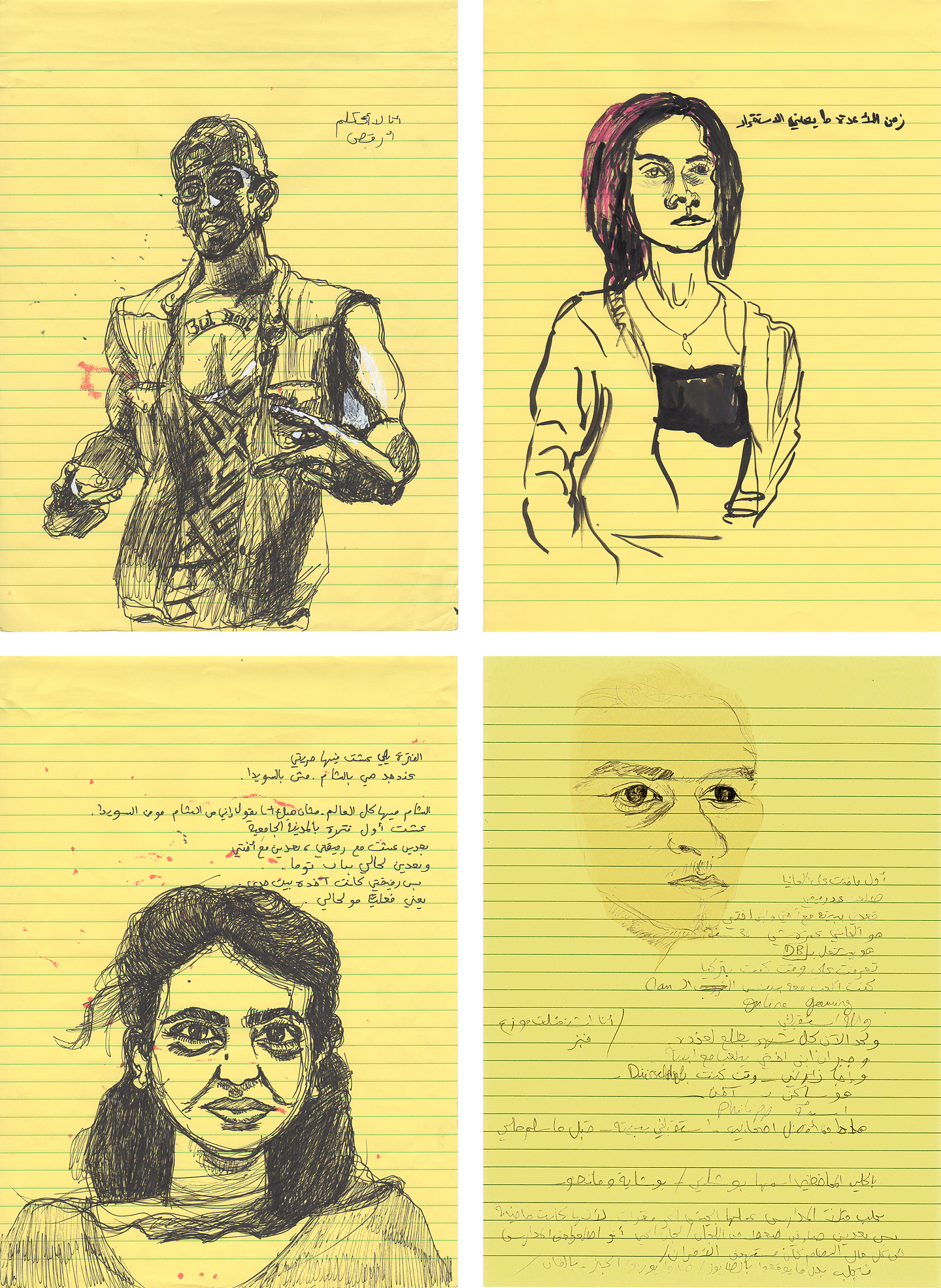

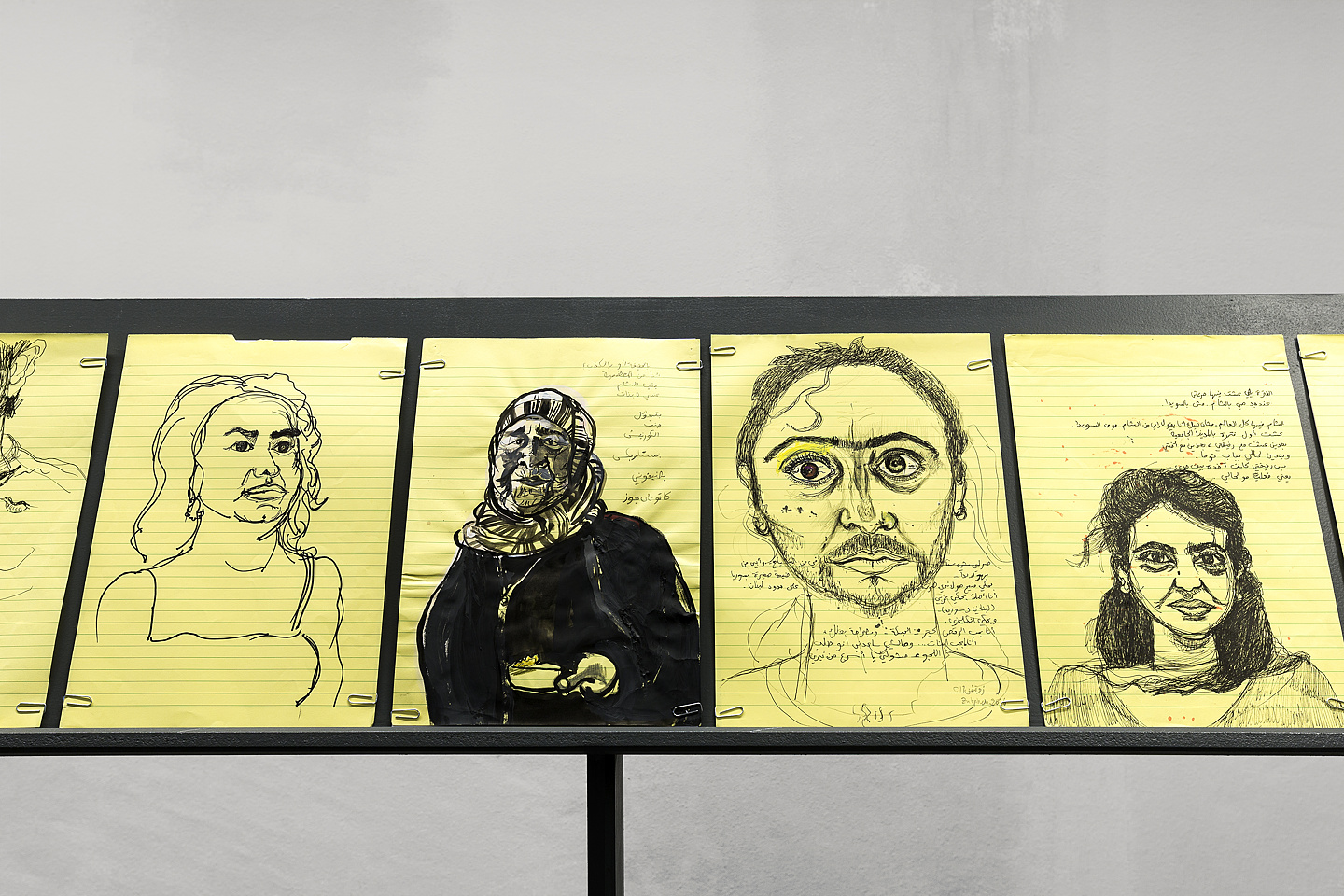

The Lebanese-Dutch artist Mounira Al Solh, born in Beirut in 1978, presents a series of portraits at documenta 14 under the title “I Strongly Believe in Our Right to Be Frivolous.” The portraits are made through encounters in Kassel and Athens (as well as other cities) with Middle Eastern and North African migrants, who have made—or are making—the transition from the status of refugees into citizens.

Including text, drawings, embroideries, and a sound installation, the project began in 2012 as “time documents” of the Syrian and Middle Eastern revolutions and subsequent crises. “I Strongly Believe …” approaches the topic of (forced) migration on the level of oral history: an ambiguous historiographic category that escapes more formal archival processes, yet an undeniably tenacious one because knowledge is conveyed through people themselves. The project and the production of these portraits follows the artist and vice versa as she connects to local communities in the cities she visits.

The oral history of displaced individuals that Al Solh bears witness to is as much a legal account as a personal one. Many of the portraits are drawn on yellow legal paper, which serve as material indexes of the painstaking bureaucratic processes through which immigrants must go in order to obtain citizenship. The portraits map the geographies of arrival through storytelling, but also through the experience of immigration policies that deeply affect Europe’s political landscape.

The sonic elements of the work are translations of the Arabic texts in the portraits. It is hard to discern which voice belongs to which text, or even to which person the voice belongs. The ever-expanding oral history situates the stories of migrants within the informal social economies in which trauma, relief, fear, anxiety, joy, and hospitality unfold.

—Hendrik Folkerts