What happens if polar tension is released?

When the pull of gravity is tampered with?

When the continents drift and form new constellations of land and water?

What might the world look like if you could peel away the top surface of the globe to reveal another world beneath?

These questions of radical displacement, where the laws of nature are deliberately placed in a state of flux, reveal new possibilities and open up potential for new knowledge. They are also the questions of Agnes Denes, whose visionary artistic practice delves deep into science, philosophy, and the human condition. Born in Budapest in 1931 and having lived in New York since 1954, for Denes “art exists in a dynamic, evolutionary world where objects are processes and forms are dynamic patterns, where measure and concepts are relative and reality itself is forever chaining.”

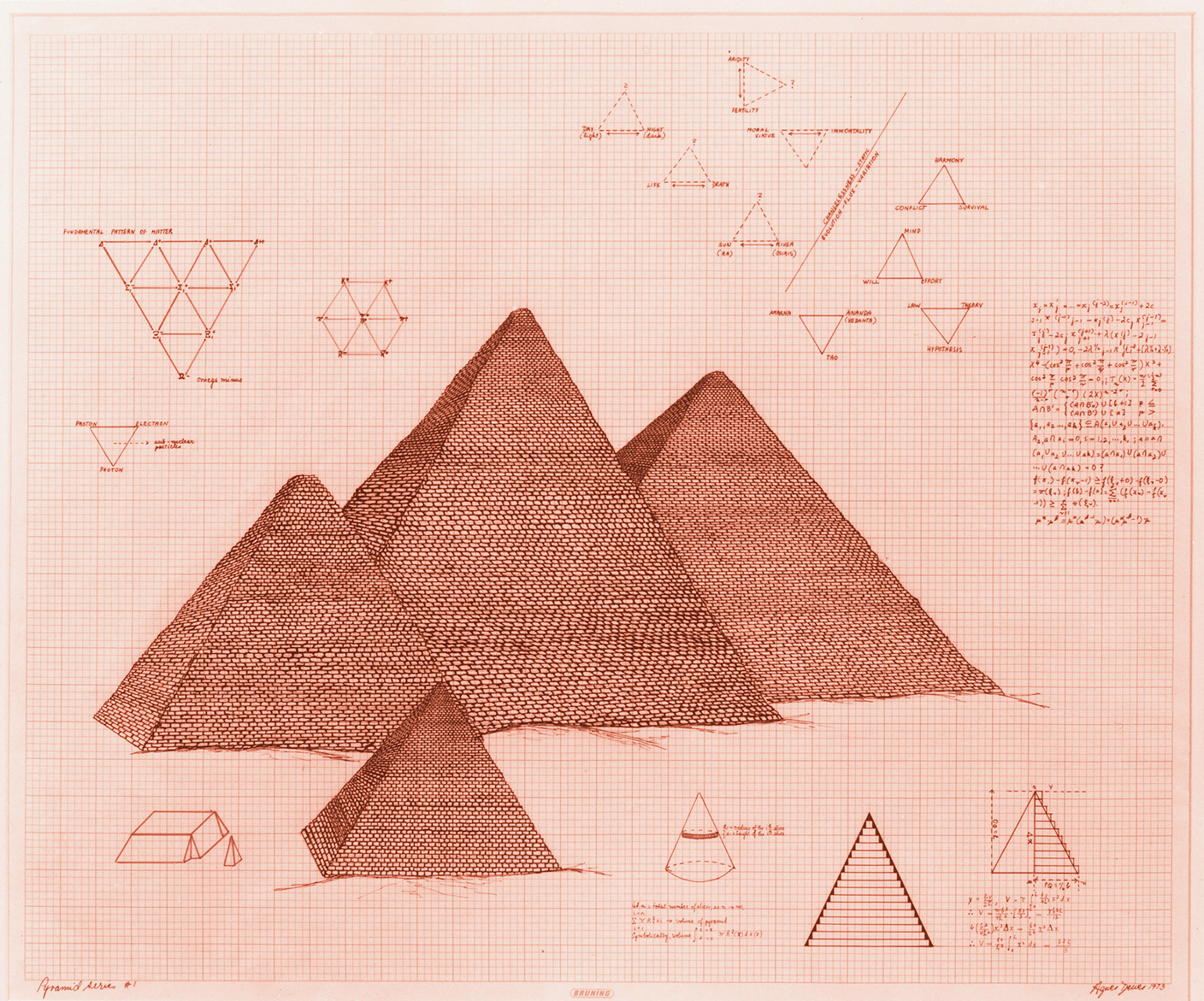

Denes’s study into dynamic patterning is best witnessed in her series of pyramids: there are pyramids created from 11,000 fir trees, blocks of crystal, and microscopic piles of human dust; there are drawn pyramids that morph into snail shells, flying birds, and manta rays. Some are made of Plexiglas filled with oil and polluted water, others are prototypes for future cities. One of the largest realized is The Living Pyramid (2015), installed at Socrates Sculpture Park, Long Island City, New York. Constructed of stacked wooden terraces filled with soil and thousands of various living plants, the sculpture arcs nine meters up toward the sky. It is a social structure. Social because the planted material conveys ideas of evolution and regeneration; the work also cultivates a micro-society of people responsible for its planting and ongoing care.

The pyramids are part of Denes’s larger visual philosophy, one that collectively uncovers invisible systems and reveals ambiguities and analogies between different forms in nature. It also offers a means to better understand ourselves, as for Denes, nature is often a stand-in for humanity. This relationship was evoked in Wheatfield – A Confrontation, a six-month project in 1982, where two acres of New York’s Battery Park landfill were cleared by hand and planted with wheat. The grain stalks ripening under the shadows of the then-standing World Trade Center towers became a sign for the paradoxical effects of globalization: how increased trade and capital flows produce drastic inequities. The harvested seeds from Wheatfield were later distributed through networks worldwide as a way to draw attention to food crises. As Denes reflects on the work, the seeds were more than utilitarian: “they represented misuse of land, greed, and misplaced priorities.”

—Candice Hopkins