Roee Rosen—painter, novelist, and filmmaker—is an astute critical voice in Israel. While his work deals primarily with the representation of desire and structural violence, Rosen, born in 1963, has created an artistic universe that treacherously undermines the normative implications of identities and identifications through fictionalization, irony, and revision. In untold variations, he typically links current Israeli and world politics with mythical and political references to European and Jewish history. Using a vast array of fictional characters and iconographic motifs and codes, Rosen frequently refers to, and transforms, not only the canon of the historical avant-garde and transgressive traditions from the Marquis de Sade to Georges Bataille, but also popular media, political propaganda, and classic children’s fairy tales.

Live and Die as Eva Braun, Rosen’s trailblazing installation and book of 1995–97, compel viewers to identify with and indeed become Hitler’s mistress. The work lays out a script that inverts the parameters of accepted histories and gives voice to the absurdity and obscenity of what is deemed unspeakable. Stringent on the textual level of the script, and delirious and hallucinatory on the painterly one, the work as a whole constitutes an elaborate, provocative meta-commentary on the politics of remembrance and identity formation, specifically the use and abuse of the Holocaust in present-day Israel.

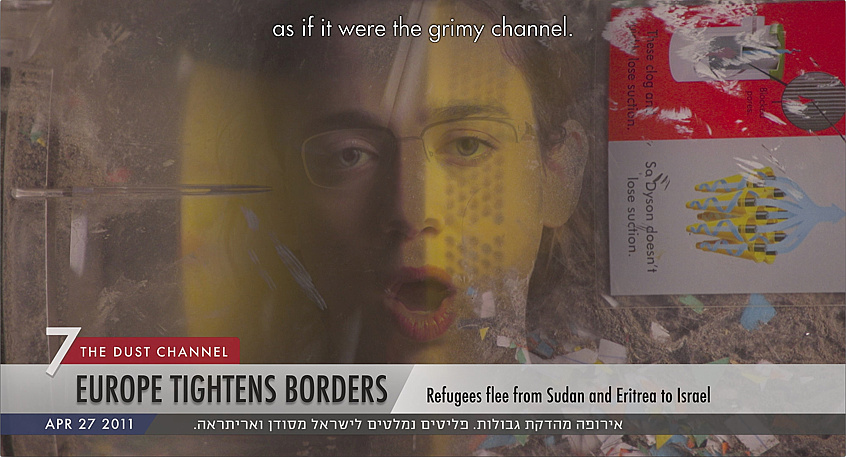

Rosen’s most recent body of works is devoted to the fictional Russian-Jewish émigré Efim Poplavsky (1978–2011), aka Maxim Komar-Myshkin. As in previous projects (notably with Belgian-born female surrealist Justine Frank), Rosen has invented a biography and an oeuvre that is marked by the severe paranoia of an artist embroiled in Russian history and politics, in particular the figure of Vladimir Putin. Rosen’s new film The Dust Channel (2016) is the final chapter in the series that assumes the artistic life of Komar-Myshkin. It is an operetta with a Russian libretto set in the domestic environment of a bourgeois Israeli family, whose fear of dirt, dust, or any alien presence in their home takes the shape of a perverted devotion to home-cleaning appliances. Rosen associates dust figuratively with sand. The desert obliquely points to specific and current forms of xenophobia. The detention center where political refugees are held long-term and unrecognized by the state is in the Israeli desert and named Holot—the Hebrew word for sand.

—Hila Peleg