Annie Pootoogook, Annie at the Sobey Awards 2006, Cape Dorset, 2006, coloured pencil, ink, 66 × 51 cm. Courtesy Feheley Fine Arts, Toronto, © Dorset Fine Arts

Annie Pootoogook was from the Arctic near the North Pole. Her community is called Kinngait in Inuktitut—the language of Inuit people—and Cape Dorset in English. Annie passed away a few days ago. Police found her body washed up on the shores of a river that courses through Ottawa, Canada’s capital city. She was forty-seven-years old.

When Annie’s drawings started making their way to southern audiences, at first viewers didn’t know what to make of them. Intimate and quotidian at the same time, her works were raw, emotive, touching, sometimes erotic, tragic, and funny. They documented still lives of her grandmother, fellow artist Pitseolak Ashoona’s black-rimmed glasses with the same care and detail as domestic scenes of a family sleeping together in their summer tent. Indeed, the foundation of Annie’s early art education was the many hours she spent watching Ashoona drawing in her room. She later picked up some of her grandmother’s narrative threads, creating drawings that were personal and autobiographical at a time when the subject of many of the prints and drawings by Kinngait artists still centered on hunting, animals, camp life, and Inuit mythologies, scenes that had a strong market among southern collectors.

Through her drawings, Annie let us into her life in all of its complexities. She documented her family watching “The Simpsons,” listening to the weather report on a transistor radio, her boyfriend trying to hit her, a child taking its first steps much to the delight of its mother and father, as well as many singular objects—a pen and pencil, a bra, and a camp stove, to name a few. Many of her drawings touch upon the devastation that alcoholism and suicide—both of which occur in epic proportions in the north—where communities are still healing from the open wounds of colonialism and the radical severing of lives once lived in rhythm with the land.

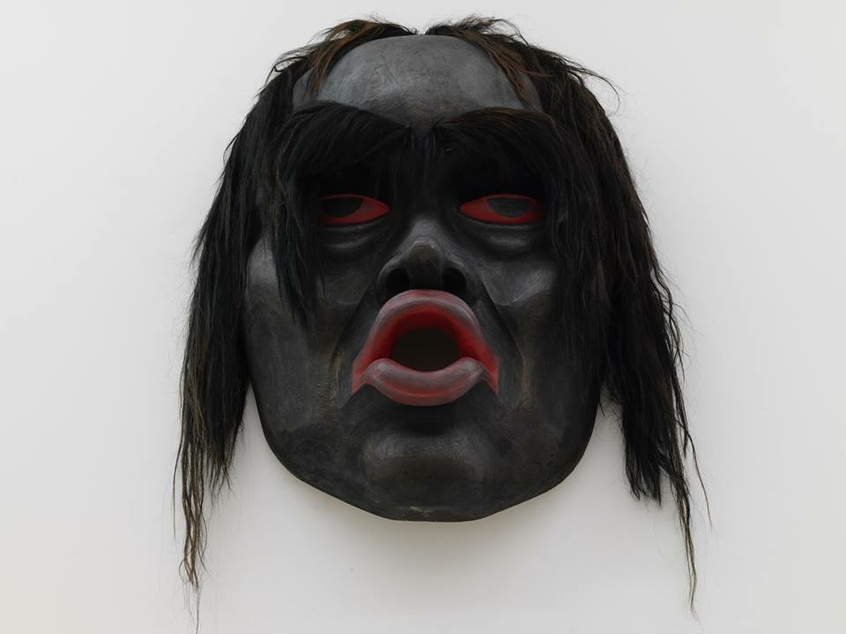

Annie achieved great acclaim during her life. Her drawings were featured in the 17th Biennale of Sydney (2010) and countless solo and group exhibitions across Canada. She is best known for winning the 2006 Sobey Award, the most prestigious prize for artists under forty in the nation. Shortly thereafter, she was invited to be a part of documenta 12 (2007). Her inclusion made national headlines and made her community proud.

Annie was always humble. She was kind and was generous. She moved to Ottawa a few years ago to start her life over again. Yet what was meant to be a new beginning marked an untimely end. Annie struggled with the success that her practice brought—for a period it was as though everyone wanted a piece of her when all she wanted was to escape from the attention and from the personal demons that always seemed to follow a little too closely.

In the Arctic there is a well-known story about a creature, half-fish, half-woman. She is called Sedna. Sedna was meant to meet her death after her father tried to drown her in the ocean for marrying someone he didn’t approve of. Despite his cruelty (he cut off her fingers one by one as she clung to the edge of his boat), she became the mother of the sea. In turn, each of her fingers grew to become the first seals, walruses, and whales.

I imagine that Annie now swims alongside Sedna, that they now provide strength for one another.