Enfleshment of Memory

We can sympathize with the distress which excessive hunger occasions when we read the description of it in the journal of a siege, or of a sea voyage. We imagine ourselves in the situation of the sufferers, and thence readily conceive the grief, the fear and consternation, which must necessarily distract them. We feel, ourselves, some degree of those passions, and therefore sympathize with them: but as we do not grow hungry by reading the description, we cannot properly, even in this case, be said to sympathize with their hunger.

—Adam Smith, The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759)

Dimitris Harissiadis, Social Insurance Institute (IKA) Piraeus (1942–43), digital scan from 6 × 6 black-and-white negative

Hunger, Thomas Malthus and Adam Smith tell us, independently from each other and with completely different concerns, is a man-made condition, the result of the ecosystems of societies—society drives itself to overpopulation and then hunger claims the superfluous lives. Historian James Vernon recalls the story of Charles Trevelyan, assistant secretary to the British Treasury, who handled the famine in Ireland in such an exemplary manner (so the English thought) that he was knighted. Trevelyan considered the famine to be a “direct stroke of an all-wise and all-merciful Providence. … remedy … cure” to the problem of overpopulation of Ireland. Even if not directly a matter of biopolitics, Trevelyan’s thinking certainly carried with it a Smithian twist—the invisible hand straightened out by Malthusian mathematics.

By the end of World War I hunger had acquired an ethical character, Vernon says; those who survived it were considered morally superior. A rather strange notion that appears in the most unexpected places—imperial Britain in the cases of the famines in Ireland and India; in Tadeusz Borowski’s writing about the “Greeks” in Auschwitz:

We sit down in the narrow streaks of shade along the stacked rails. The hungry Greeks (several of them managed to come along, God only knows how) rummage underneath the rails. One of them finds some pieces of mildewed bread, another a few half-rotten sardines. They eat. … their jaws working greedily, like huge human insects. They munch on stale lumps of bread.

The Greeks who caused such deep disgust in Borowski and whom he despises for eating those stale lumps of bread in Auschwitz in 1943 are the Sephardim transports. In addition to Greek communists, resistance fighters, Gypsies, forced labor, and some 1,500 clergy sent to the various German concentration camps, the vast majority of Greek Jews, around 60,000, perished there, decimating the Jewish communities in Thessaloniki and Ioannina.

Dimitris Harissiadis, Social Insurance Institute (IKA) Piraeus (1942–43), digital scan from 6 × 6 black-and-white negatives

Dimitris Harissiadis, Social Insurance Institute (IKA) Piraeus (1942–43), digital scan from 6 × 6 black-and-white negatives

Greece entered World War II when Italy issued an ultimatum for free passage on October 28, 1940. Between October 1940 and April 1941, the war was fought on the mountains along the Albanian border, as the Greek army made steady advances. On April 6, however, the German army began its sweep through Greece in the course of six days. Germany then established a tripartite occupation, with the Italian and the Bulgarian armies, which destroyed the country both financially and politically. In order to feed itself and support its North Africa campaign, the German army quickly requisitioned the harvest. The allies, hoping to pressure the occupying forces and the Kommandantur, moved to blockade Greece. The famine that followed in the autumn of 1941 and winter of 1942 was unprecedented, even in this small, always poor, always dependent country, and led to the establishment of Oxfam. Estimates vary as to the numbers of those who died but they hover between 100,000 and 450,000. The famine conditions in Greece at the time were comparable to the conditions of the most abject hunger that had appeared in India in 1876–78, as well as to the postwar conditions in Bangladesh, in Biafra, in Ethiopia (and perhaps currently in Aleppo). Indeed, the experience of the famine remained seared onto the social memory of Greece for many decades, until the brief and singular economic amplitude of the early 2000s set it aside.

Photograph from Kostas Paraschos, He Katoche: Photographika tekmeria 1941–1944 (The occupation: Photographic documents 1941–1944 [Athens: Hermes, 1974])

The enfleshment of its memory has been almost epigenetically transmitted, precisely because the famine was not fleeting or invisible. Along with its visuality, such hunger carried smell: the smell of escaped excrement caused by vitamin deficiency, the smell of hunger that escaped from the mouths, the smell of death that permeated everything. It carried sounds: the sound of the horse-drawn municipal carriage collecting the bodies of the dead who had dropped in the middle of the street; the sound of humans going through the rubbish in the hopes of finding a moldy breadcrumb, a piece of cheese discarded by the occupiers. The sound too of the hungry uttering a single word: πεινάω (peináo: I am hungry). The scene relayed by Borowski in Auschwitz had happened before, of course, to both Jewish and non-Jewish Greeks, in the streets of cities and towns throughout their own country during the occupation. Mansions, wedding bands, gold teeth, family silver and silk, deeds to family farms, the only pair of shoes or the last family embroidery: all were turned over to the hands of the black marketeers for a tin of olive oil, a pound of butter, a bushel of wheat, or a piece of meat—usually sourced from among the companion or burden animals, the cats, dogs, the old, overworked donkeys. Soup kitchens guaranteed an average of 400 kilocalories a day.

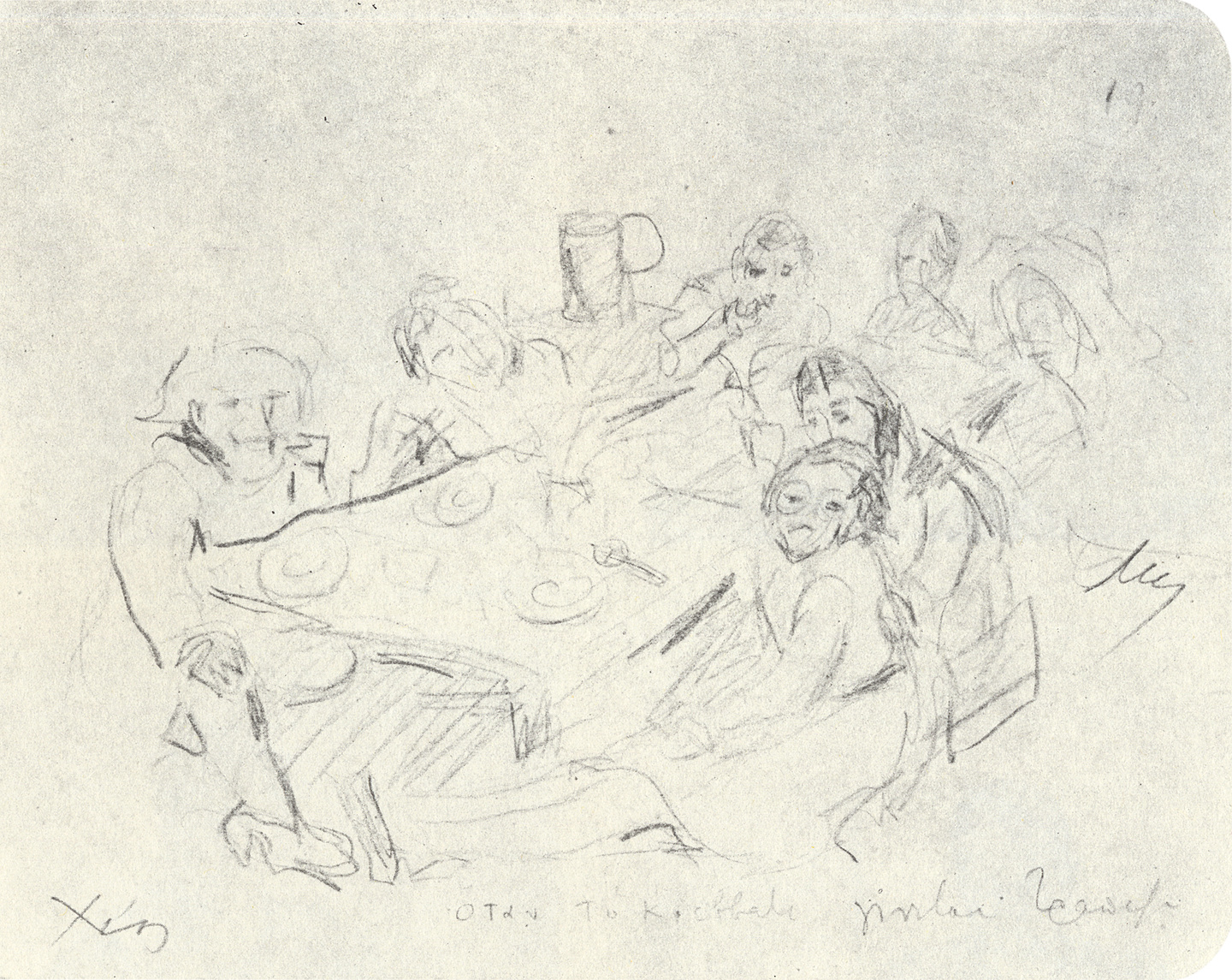

Katerina Hariati-Sismani, When the Bed Transforms into a Table (1948–52), pencil on paper, 16 × 20 cm. Exile Museum, Athens

In Greece, it was the synesthetic dimensions of hunger being narrated over and over again that transferred its experience and twinned it with the very memory of being. It was a famine that produced locutions of despair readily recognizable for decades afterwards in afterlives that organized socialities, subjectivities, and humanities. Even after the blockade was broken in October 1941—initially by the Turkish cargo ship SS Kurtuluş, with relief of a symbolic 1,700 tons of wheat, then lifted entirely in February 1942—this only changed the Greek situation of λιμός (limós: famine) to a more entrenched πείνα (peína: hunger). Hunger came to be part of the political management of the Axis powers; the Waffen-SS in particular undertook acts of retaliation against civilian populations in which the inhabitants of entire Greek communities and villages were executed, and their houses and fields burned to the ground. This burning ensured not only the immediate cessation of life but also the discontinuation of any possibility for recovery. Kommeno, Kolymbari, Distomo: tiny villages that no one would ever know outside of their immediate environments came to become part of the exemplum of barbarity. This was a biopolitics of violence, not a biopolitics of hegemony.

In 1945 Osbert Lancaster took one look at Distomo and concluded that even before its obliteration by the Waffen-SS, in 1944, “the village must always have worn a sufficiently poverty-stricken aspect.” Most villages did, even before the war. In Greece, hard agricultural work was carried out not by well-fed farmers—if such ever existed before the introduction of agribusiness and government subsidies—but by lean men and women who had normalized their limited sustenance.

Greece has never been an affluent country, and foodstuffs have rarely been abundant—a reality that has never escaped its structural conditions. The terrain is mountainous or arid, the soil is too thin or too sandy, crops failed or were owed to the bank or the protector, plots were too small or too rocky, ruling politicians cared more for their own interests than those of the citizens, and the old elites who built and financed the operations of the first public and boarding schools, hospitals, poor houses, and public buildings in the country were replaced by a class that kept its money close to its chest. That said, πεινασμένοι (peinasménoi: hungry) came to index the insatiable postwar desire for everything—money, food, sex, property—that finally found its realization in the galloping surreal capitalism of the late twentieth century and beyond.

Hunger did not end with the war, however. During the Greek Civil War, from 1946 to 1949, which followed liberation, concentration camps for leftists and communists were set up on three islands: Makronisos was for army conscripts and officers, Yaros for civilians, and Trikeri for women. Originally organized by the British but taken over by the U.S. in 1947 and funded largely through the Marshall Plan, the camps were organized on the premise of reeducation and rehabilitation.

Utensils made in the exile camp on the island Agios Efstratios, 1947–52: aluminum plate, tin cup, and speargun by exiled author Chronis Missios. Exile Museum, Athens

Run mainly by wartime collaborators with the Nazis, the Greek camps followed the paradigm of hunger established during the war itself. Hunger became one of the modalities of this political realignment death project. Despite the systematic, continuous, and methodical tortures and forced labor, the daily caloric allowance for each camp prisoner hovered around 1,800 kilocalories per day, 1,000 of which was to be sourced from bread. The old exile islands, remote and largely inaccessible, that had been used by the pre- war liberal and authoritarian governments were cycled in again, and leftists were sent and kept there until 1963, left largely to their own devices as to the procurement of food and medicines. They improvised by creating cooking utensils and equipment from scraps—making a speargun for fishing out of the legs of an ironing board.

The devastation brought upon the country by the occupation and the Civil War resulted in the long-term dilapidation of social life in Greece. Although funds from the Marshall Plan in the 1950s allowed the newly reorganized Greek middle class to think again about the possibility of a relatively comfortable life, the lower socioeconomic strata still lived in wartime squalor and continued to experience hunger and malnutrition regularly. In the postwar years, the large relocation of agrarian populations to urban centers further contributed to the inability of the country to come close to self-sufficiency in its food production, and it was not uncommon for families to devote up to 70 percent of their income to food sourcing, primarily legumes, potatoes, and greens. According to the journal Neos Kosmos, daily food consumption at this time remained lower than the average during the period 1934–38.

But how to engage in the representation of hunger, one that would neither objectify nor trivialize the human subject? Or, differently thought, should such a representation only be self-representation? What are the ethics in representing the suffering of others? What are the limits and the vicissitudes of inter-subjectivity? Katerina Hariati-Sismani (1911–1990), a Berlin-trained painter who was exiled to the camps on Chios, Trikeri, Makronisos, and, eventually, to Agios Efstratios, attempted a response: While on Trikeri, in a story that Hariati-Sismani related later to her son, Harilaos Sismanis (founder of the Exile Museum in Athens), the exiled women learned about a Jewish mother in the Theresienstadt concentration camp who had died of hunger while nursing her twin children. Hariati-Sismani was so moved and shaken that she put the image as she imagined it to paper in a charcoal drawing. When she was released from exile herself, Hariati-Sismani was able to turn the initial drawing into a small bronze statue that doubles the experience of hunger experienced by both the maker and the subject.

Equally moved and horrified by the hunger in Greece, and engaged with the question of its representation and iconography, was the artist Anna Kindynis (1914–2003). Although Kindynis was never persecuted—she was spirited out of Greece to Paris in December 1945 in a saving transport of intellectuals and artists organized by the Institut Français d’Athènes through a fellowship that came to be known as Mataroa, named after the ship that carried them—her haunting works in charcoal and pencil depict the excruciating results of the famine. Her many drawings of dazed, starving children, indelibly caught up in the violence and hunger that war brings, foreshadow recent images that have emerged from Syria, particularly the widely circulated photograph of Omran Daqneesh, yet another child subject of yet another brutal war.

Hunger is, indeed, a man-made disaster (increasingly a woman-made one, too). Whether it is the result of environmental catastrophes or war—military or financial—matters little. As a result of the war in Syria, the seed bank of ICARDA (International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas) in Aleppo, fearing that it might lose its collection of seeds specially adapted to arid environments, recently requested replacements from the Svalbard Global Seed Vault in the Norwegian Arctic. This is the first time that Svalbard has agreed to release seeds—because the threat to ICARDA’s collection is not unsubstantiated. Seed banks in Afghanistan and Iraq have been devastated by the recent wars there. But what about financial wars? “You don’t eat much,” the young man said to his even younger guest, a girl not yet out of high school, as painfully thin as a rail. “There are some days when my father doesn’t even make two euros at his shop, so there are times that we go for two or three days without food at home and my stomach has shrunk; I can’t eat much.” Her response was as matter-of-fact as a butcher’s knife. Words spoken in Greece in the summer of 2015.

Graph charting population figures from The Sacrifices of Greece in the Second World War (Athens: Greek Ministry for Reconstruction, 1946). Book composed by architect Constantinos A. Doxiadis

A special thanks to Kelly Tsipni-Kolaza, Constantinos Papachristou, and Harilaos Sismanis for their research help with this essay.

Works Cited

Anonymous. “Anaskopiseis.” Neos Kosmos 5 (ΜMay 1954), p. 64.

Black, Maggie. A Cause for Our Times: Oxfam the First 50 Years. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992, p. 9.

Borowski, Tadeusz. “The World of Stone.” In This Way for the Gas, Ladies and Gentlemen. London: Penguin Books, 1976.

Bournova, Eugenia. “Deaths from Starvation: Athens Winter of 1941–1942.” In The Price of Life: Welfare Systems, Social Nets, and Economic Growth. Edited by Laurinda Abreu and Patrice Bourdelais. Lisbon: Edições Colibri, 2008, pp. 141–62.

—“Propolemiki diaviosi kai katochiki epiviosi stin Athina: Istoria kathimerinis zois” (in collaboration with Stavros Thomadakis). Ta Istorika 41 (December 2004), pp. 455–70.

—“Surviving in Athens during the German Occupation.” In The Experience of Occupation, 1931–1949. Proceedings, International Conference organized and sponsored by the International Committee for the History of the Second World War, the Chinese National Association for the History of the Second World War, and Wuhan University, China, April 14–16, 2008. Wuhan: Wuhan University Press, 2010, pp. 299–308.

—“Thanatoi apo peina: I Athina to cheimona tou

1941–1942.” Archeiotaxio 7 (May 2005), pp. 52–73.

Hionidou, Violetta. Famine and Death in Occupied Greece 1941–1944. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

“ICARDA Receives Gregor Mendel Innovation Prize for Ensuring Safekeeping of its Genebank Collection.” The International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA), May 19, 2015. Online: www.icarda.org/update/icarda-receives-gregor-mendel-innovation-prize-ensuring-safekeeping-its-genebank-collection#sthash.fDcFxx62.cIIfx47Z.dpbs.

Lancaster, Osbert. Classical Landscape with Figures. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1949.

McClintock, Michael. Instruments of Statecraft: U.S. Guerrilla Warfare, Counterinsurgency, and Counter-Terrorism, 1940–1990. New York: Pantheon Books, 1992.

Norwegian Government. Online: www.regjeringen.no/en/topics/food-fisheries-and-agriculture/landbruk/svalbard-global-seed-vault/id462220/.

Panourgiá, Neni. Dangerous Citizens: The Greek Left and the Terror of the State. New York: Fordham University Press, 2009.

Sen, Amartya. Poverty and Famines: An Essay on Entitlement and Deprivation. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1983.

Skalidakis, Yannis. “From Resistance to Counterstate: The Making of Revolutionary Power in the Liberated Zones of Occupied Greece, 1943–1944.” Journal of Modern Greek Studies 33, no. 1 (May 2015).

Smith, Adam. The Theory of Moral Sentiments. New York: Gutenberg Publishers, 2011. Reprint of 1790 London edition.

“Social and Economic History of Athens.” Online: www.social-history-of-modern-athens.gr/en/.

Stathakis, George. The Truman Doctrine and the Marshall Plan: The History of U.S. Assistance to Greece. Athens: Vivliorama, 2004.

Vernon, James. Hunger: A Modern History. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007.

—“Hunger, the Social, and States of Welfare in Modern Imperial Britain.” Occasion: Interdisciplinary Studies in the Humanities 2 (December 20, 2010). Online: arcade.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/article_pdfs/Occasion_v02_Vernon_122010_0.pdf.