Walking with Nandita

Here was the soup. It was a plain gravy soup. There was nothing to stir the fancy in that. One could have seen through the transparent liquid any pattern that there might have been on the plate itself. But there was no pattern. The plate was plain.

—Virginia Woolf, “A Room of One’s Own” (1929)

New York City, 157th Street

I am trying to think “language or hunger,” but I inevitably supplant hunger with eating, not eating, and shitting, all of which differ from hunger. Hunger is abstract, and my mind goes to things that are concrete.

Alejandra Pizarnik’s Diarios are pure poetry. I made the rounds of Paris bookstores till I found a single copy of the beautiful José Corti paperback with Pizarnik’s face on it. She is pulling a book off a high shelf and staring back at the camera, at us. I kept this book on a skinny Chippendale bookcase next to my bed with the cover facing out for several years so that I might meet her soulful gaze daily. I read a hundred pages or so before standing the book up like that. I was blown away by the diaries, but they are also inescapably dark. For Pizarnik, suicide was not a question of if but when, and she wrote about it almost daily, as though death was her little friend. She envied Virginia Woolf.

Hungry, thirsty, in need of stimulants, Pizarnik’s appetites and cravings were outsized. She hated herself after lunch and dinner, and wrote: “To not eat I must be happy. And I cannot be happy if I am fat.”

In my bones I understand Pizarnik’s tautology, but my mind needs to metabolize it over and over. I memorize it; it slips away.

Here is Alison Strayer’s lovely spin (Pizarnik’s idea somewhat teased out): “to write, driven by inspiration, you have to be thin and fleet, and to be thin and fleet you have to write, driven by inspiration. A conundrum.”

In her 1975 film Je tu il elle (I, You, He, She), Chantal Akerman shovels powdered sugar into her mouth while writing lying down—she is composing and revising a very long letter. The entire bag of sugar is ingested, spoonful by spoonful, to fuel the manic, around-the-clock writing. As viewers of her film, we bear witness to what is surely one of the most sustained and inspired moments of self-abuse in the service of avant-garde, materialist cinema.

Conversely, when Virginia Woolf succumbed to periods of so-called madness, the treatment consisted of denying her both language and hunger. She was not permitted to read or write, and she was made to consume excessive quantities of meat and milk. Her intellect was starved, and her naturally thin frame was fattened against her will. According to her great-niece, Emma Woolf, the regimen consisted of: “Four or five pints of milk daily, as well as cutlets, liquid malt extract and beef tea.”

Woolf appears gaunt in some of her photographs. Like many writers, she probably didn’t experience hunger when she was writing. She was prolific, and it is likely that language evacuated bodily hunger for a good portion of her life. Her great-niece has speculated that Woolf was anorexic, but if that’s the case I’d wager only in the sense that she had no appetite. Though who knows. Forced to bulk up, she might have developed a fear of fat.

Woolf wrote about food, most famously in “A Room of One’s Own.” She describes the bland meal served in the dining hall of a women’s college and speculates on the necessary (and there absent) connection between stimulation of the palate and stimulation of the mind. In “Evening over Sussex” she describes the comfort food that awaits her after a long day of travel and walking, and no doubt writing parts of the namesake essay in her head.

In the episode of Ulysses known as “Calypso,” which begins with a very large printed “M,” Leopold Bloom, after his breakfast of grilled kidneys, famously retires to the outhouse where he reads two columns of the newspaper and produces one or two excremental pillars of his own. Evacuated and grateful, he nonetheless envies the writer of the article who was paid “at the rate of one guinea a column.”

American artist Pope.L masticates the Wall Street Journal and allegedly washes it down with milk while sitting atop a toilet perched on a tower.

Canadian poet Elizabeth Smart, living in England, makes a New Year’s resolution list for the year 1945. Below are the first seven items listed:

1) Keep a diary or Daily Notebook.

2) Keep Accounts and never spend more than £20 a month on living (and partly living).

3) Keep the children Prettily dressed always.

4) Keep Everything Clean.

5) Answer all letters within three days.

6) Keep bowels open.

7) Have a baby. [checked] Sebastian 16 April 1945.

Discipline, money/frugality, cleanliness, punctuality, open bowels (which I’m sure Smart meant literally, but I’d also infer an implied wish for writing to flow more readily), and having a baby form the top priorities. Smart had four babies all by the same man, George Barker, who’d never consent to live with her, nor would he let her go, thus keeping her in a decades-long state of unrequited craving and misery.

Writing at the end of her life, in a state of relative isolation, photographer Julia Margaret Cameron was clear about her needs: “I feel it is as necessary to give a hungry heart a letter as a hungry body a slice of bread.”

New York City, 42nd Street

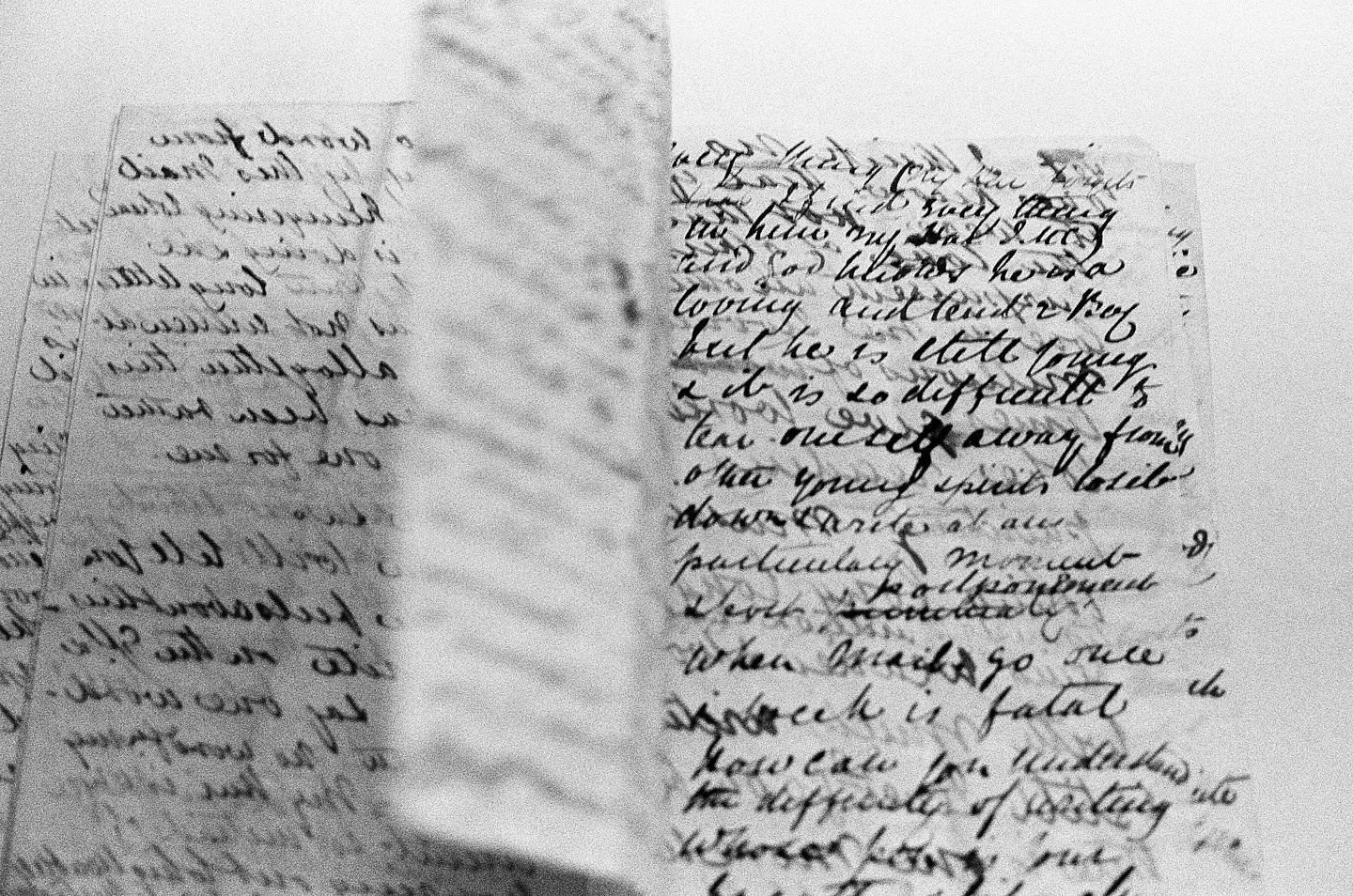

The Berg Collection at the New York Public Library owns four letters in Cameron’s hand, mailed two days apart from Kalutara, Ceylon, in February 1878. They all concern the second marriage of her niece, Julia Prinsep Duckworth (née Jackson) to Leslie Stephen, who would become the parents of Virginia Woolf. One letter is eighteen pages long, on onionskin paper, folded in half and hard to decrypt because the ink bleeds through front to back. I badly want to photograph these 138-year-old letters, but before doing so, have to inquire after an obscure heir. No rights-holder materializes, and two months later I sign a “hold-harmless” form, gaining permission to take twenty pictures of Cameron’s letters. Also in the Berg Collection are two of her photographs of the same niece, Julia, as a young woman, one before her first marriage to Herbert Duckworth, and a second, showing her in a black mourning dress trimmed in crêpe. Her thirty-seven-year-old husband died three years into the marriage, leaving her a widow, pregnant, and with two children. My arrival at the library was set in motion a few months earlier via a fortuitous encounter in a cemetery in Kolkata.

Kolkata

A group of visitors to the city, we meet up with our hired guide and walk west on South Park Street as the guide volubly narrates the history of its colonial-era department stores, cafés, banks, and bookstores. This is a preamble; the real destination is the South Park Street Cemetery, a truly haunted site of magnificent, crumbling tombs, and the final resting place of nineteenth-century British colonials. The monuments are extravagant structures in the style of Greek temples and other ruins; the largest and tallest memorial being a replica of an Egyptian pyramid. Surrounded by palm fronds, and appearing to emerge from a cloud of thick smoke, the tombs remind me of the jungle scenes in Apocalypse Now. The smoke is generated by the many small fires that dot the cemetery and lend it its distinctive smell of burning eucalyptus. Our guide is eager to point out the graves of women who died young and who were beautiful, but I’ve stopped listening and wander off on my own, taking in the sepulchral landscape, my eyes focused on the small screen of my camera set to “record.”

On our way out, I’m given a booklet-guide to the cemetery, and it is here that I note the name of one of its residents: Thomas Prinsep, who died in 1830 of an equestrian accident. I immediately connect him to May and Thoby Prinsep, photographed by Julia Margaret Cameron, and to Julia Prinsep Jackson, the photographer’s niece and favorite model. Almost as quickly I remember Cameron’s Anglo-Indian roots, her birth in Calcutta, and her colonial life as the wife to Charles Hay Cameron, a man twenty years her senior and a higher-up in the British government in India. A practicing Christian and a memsahib for sure, Cameron was also an eccentric and a great charmer. Her flowing velvet robes were said to reek of darkroom chemicals, and her hands were stained black with the same. Remembered for her persuasiveness, her long letters, her generosity, Cameron was a highly energetic woman who once spearheaded a campaign for the Irish in 1845 during the famine years, raising £14,000 in aid—an immense sum at the time.

On our way back from the cemetery, we pass a sidewalk soup kitchen dispensing ladles of dal. A long line of people wait, holding containers. One man seated by the road does not have a bowl and eats his serving from a bulging plastic shopping bag.

Sarnath

Walking with Nandita Raman at Sarnath, the Buddhist monastery ruins just outside Varanasi, she catches sight of a woman harvesting grass and says: “There’s the scene from Phantom India.” Immediately I recognize the opening shot of Louis Malle’s 1969 film, where camera and crew approach two women foraging in a patchy field. The women move crab-like over the dusty ground, stuffing clumps of grass into sacks strung over their shoulders. One of them draws her sari over her face and does her best to evade the camera. Phantom India, with its painful meditation on the intrusion and indiscretion of the camera, remains a touchstone documentary work, and the thought crosses my mind to film this contemporary version identified by Nandita. I picture aliveness and engagement and a meta-take on Malle, but I keep on walking. I default instead to taking docile, boring photographs of inanimate objects with my digital camera. These photos—or rather, “data”—live on tiny, plastic SD cards scattered around my apartment, which is also my studio, and I have a hard time taking them seriously until the day I need to locate something, at which point a small panic then ensues.

Calcutta

Julia Margaret gave birth to six children, each of whom were sent to England to be educated at as early as four years of age—all anxiety-ridden separations for the mother, who thereafter lived in a state of chronic worry over her children’s well-being. Cameron’s lifelong identity was unequivocally that of “mother” (she also adopted at least five children) until the age of forty-eight, the day her eldest daughter and son-in-law gave her a camera, at which point everything changed. Cameron struggled massively with the unwieldy technology, still in its infancy, of wet collodion emulsion on large, glass plates. There were disappointments, but she labored and soon began to produce the beautiful portraits for which she is best remembered, those of her illustrious friends and the photogenic members of her household.

I see Cameron as an ambivalent figure in the annals of the medium. In the photo history classes I took throughout the 1980s in Montreal and San Diego, she was often conveniently positioned as an upper-class hobbyist who trained her lens on her social and family connections, and whose work easily migrated to kitsch and sentimentality. She was bossy, driven; she corralled her subjects. Her appetite for opportunities to photograph the “famous men and fair women” of her day was uninhibited. While she charmed many, she also had her detractors. Yet she was a resolute pioneer of nineteenth-century photography, one of its earliest practitioners, and one of only a handful of women in the field. She was driven by a passion to make her work, and did so in a state of constant, genteel poverty, dependent on the generosity of richer (and eventually resentful) friends and family.

Within six months of beginning to photograph, in an effort to fund her vocation, Cameron had arranged a contract to sell her work through the London print dealers Colnaghi, a professionalism almost unheard-of in women of her social class. Colnaghi produced their own editions of the prints, while Cameron endeavored to get the mounts signed by her famous sitters (Tennyson, especially) as this helped with sales, though only marginally. In her catalogue raisonné there is a note in Cameron’s hand arguing against the selling of second-rate prints or the discounting of her successes, which presumes buyers were reluctant to pay full price. Nor did it help that, ever impulsive, Cameron was known to give away much of her work.

Varanasi

With Nandita I climb a steep staircase to the ashram of Sri Anandamayi Ma to hear small, mop-headed girls chant at dawn. Dressed in pale yellow shifts and saris, these young renouncers enter single file, bow to a shrine, then sit cross-legged facing the deity. The smallest ones in front seem most earnest; one tiny girl wearing a magenta sweater over her dress and matching wool hat pulled down over her ears belts out the chants in a deep, hoarse voice. I have my camera, and it crosses my mind to record the hypnotic chanting, but this seems disrespectful. As per Hervé Guibert, who wrote about “lost photographs” and the ways they can nonetheless be reclaimed through writing, now when I think about the chanting scene, I remember it in a way I probably would not if I’d made a recording. It lives in my imagination instead of on one of those desultory SD cards, which means I can call it up in my mind’s eye and ear rather than perform the dubious “spotlight search” on my laptop for a file I probably never named, or kill my eyes by scrolling through folders. After the chanting the girls eat breakfast then gather in a courtyard to clean their metal bowls with sand.

Paris

In an interview conducted in his apartment in Paris in 1978, Rainer Werner Fassbinder says that what’s required of a filmmaker is appetite: he can make a film by reading an article in the newspaper. His material needs are minimal: he chain-smokes Marlboros and drinks black coffee. The apartment is his, but he lets other people stay in it; he says a car is useful because it can take you places, but he has few clothes and he doesn’t keep books. He can always get a copy if he wants to read something again.

Varanasi

It is easy and it thrills me to wake here at 4 am. I am rarely conscious at this hour, and it feels magical to head down to the river where many people are already gathered on the banks or in the water performing their ablutions. Very hot chai is served in disposable ceramic cups, the same ones we see turned on a wheel and set out to dry by the hundreds in yet another scene from Phantom India. We stand around chatting before climbing into a wooden boat. I take a picture of the rising sun, a fiery ball with an orange tail reflected on the river’s glassy surface, the two shapes suggesting an inverted exclamation mark. Nandita has asked her friend Ajay to be our guide; he is accompanied by his twelve-year-old daughter who barely speaks but looks and watches and absorbs her father’s narration of the ghats, the temples, the deities, and the ancient legends from which they spring. Thousand-year-old stories and rituals are part of daily life here, and they crop up with easy familiarity in the conversation of my friends. I notice too that gesture—a nod, a downward glance—forms a huge part of the economy of communication amongst Indians. Ajay’s daughter is shy and in saying very little will offer a flick of the chin, a pointed look instead. She seems immeasurably patient on this half-day journey along the river and through the tiny, winding streets and alleys of medieval Varanasi. Water trickles through the narrow streets, creating mud; cows are everywhere eating garbage; crazy drivers on motorcycles honk relentlessly and force pedestrians and cattle to hug the walls as they attempt to squeeze through impossibly slim alleyways on their oversized machines, often with a small child aboard. Nandita yells at one of them for endangering the child and all of us with their deafening noise.

After eating street food from disposable bowls made of pressed leaves, we enter a temple enclave, and as we are looking around a man comes out of a doorway and bluntly asks Nandita, who has short hair, “How old are you?” She shoots back, with a smile, “You don’t even welcome me to the temple and right away ask me that?” He says: “You look like a child.” I am utterly charmed by Nandita’s boyish face, her lilting talk, her laughing eyes. I fantasize about making a film of her in Benares, the city where she grew up and knows everyone. Also about her partner, Shrinkhla, a pediatrician. They have known each other since high school and were married in New York wearing different styles of saris in magenta and yellow.

The Sea

On my return to New York, I look at Cameron’s photographs collected in a volume edited by Virginia Woolf and published by the Hogarth Press titled Victorian Photographs of Famous Men and Fair Women. It is prefaced by Woolf’s extremely funny, compassionate memoir of her great-aunt, including the apocryphal story of Cameron’s grandfather’s corpse exploding from a cask of rum on its homeward-bound journey on a ship from India to England, causing his wife to die of fright and the sailors to drink the rum. Decades later Julia Margaret would make a similar journey in reverse, to live out her twilight years on her husband’s coffee plantation in Kalutara, Ceylon. Woolf writes: “Two coffins preceded them on board packed with glass and china, in case coffins should be unprocurable in the East.”

Kalutara

Cameron’s catalogue raisonné ends with some beautiful photographs she took of young women in Kalutara between 1875 and 1878. Seeing them for the first time is a bit of a shock. These so-called native or ethnographic portraits by Cameron exhibit neither of her trademark allegorical or shallow focus styles (for which she was and is still criticized). Simply framed and in sharp focus, the young women, wearing saris and holding water jars, meet our gaze. Were the photos not sepia-tinted, it might be hard to place them in time.

Perhaps this is a projection, but I also sense Cameron’s fatigue in the photographs, literally mirrored in the faces of her sun-drenched subjects: older men with walking sticks, eyes half-closed (or made to look so by the long exposures); bodies more bone than flesh, glistening with sweat. Even though she spent her early years in India, the last two decades were lived in England—and now back in Ceylon, Cameron was out of her element. She had to adapt her working methods to the intense heat and humidity, and to train her eye on a radically different population from the one she’d cultivated on the Isle of Wight: the scientific, literary, and artistic circles of Victorian England. Perhaps she was also ill, as she died not long after the pictures were taken.

Kolkata

Once I was back in New York, Nandita wrote to me that she was headed to Kolkata after a stay in Laos, where Shrinkhla had been volunteering at a pediatric clinic. I asked if she might go to the cemetery and try to locate Thomas Prinsep’s grave (Thomas, one of possibly eleven “Anglo-Indian” siblings, was the brother of Thoby, who married Cameron’s sister, Sara). Nandita easily located the monument and sent a digital photo, offering to go back with a medium format camera. The idea came to me that Nandita should put herself in the photo, à la Francesca Woodman. She said she never photographed herself and liked the idea of stepping outside her comfort zone. She went back with Shrinkhla to operate the bulky camera, a Mamiya 6 × 7, but managed to grab just a few photos before she was stopped by a custodian and told: “Only cell phone pictures allowed!”

New York

After shooting my allotted twenty frames at the Berg Collection, I had sixteen remaining and decided to finish the roll in the public spaces of the library. I wandered the halls taking pictures of old phone booths, which I remember using decades ago; the women’s bathroom, unchanged since the time I shot Super 8 film there in 1990; peeling paint on the ceiling; the opulent, sky-lit Beaux-Arts atrium with its chandeliers and ornate walls; a convex mirror; sunlight on marble steps; and finally a young man on a cell phone pacing back and forth before an empty glass vitrine, his figure illuminated by one of the library’s large windows.

I processed the film and had small prints made. The grainy black-and-white shots of the library spaces had a vaguely cinematic feel. In scrutinizing what I’d hastily captured of the Ceylon letters, I discovered the phrase I began by quoting at the start of this essay, overlooked in my initial attempt to decipher Cameron’s script, about a “hunger for letters to feed a hungry heart.” Clearly homesick and missing the headiness of her former life amongst poets and painters, Julia Margaret articulated the “hunger” sentiment to her sister Mia, pleading with her to keep the flow of words coming from England.

Cameron’s work was subject to chauvinist criticism during her lifetime, and later, in the twentieth century, to a class-based critique. I absorbed some of these biases, and perhaps they underpin a lingering vacillation I feel in relation to her work; on the other hand, I can completely identify with her desire to live her life as an artist and the determination that enabled this ambition against great odds.

I never imagined I would write so much about Cameron. To put it bluntly, she is not my usual type. I’ve gravitated toward mothers in the past, but they were always the ambivalent, conflicted ones. I am not so different from the eating-disordered women I began here by talking about. I am as thin as Woolf, but as a teenager Pizarnik’s food dilemma ruled my life, and some of my behavior then was as bizarre and compulsive as Akerman’s in Je tu il elle. I thought I would write much more about Woolf, Pizarnik, et al., but appetites get displaced. In my desire for a narrative I followed a thread that began in the Kolkata cemetery, I came upon an archive, and cupidity drove me to access its contents so that I could make images, take away something, fuel a story.

Moyra Davey, Untitled (JMC in Kalutara) (2016)

Taken at the Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations

Moyra Davey, Untitled (Julia) (2016)

Taken at the Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations

Moyra Davey, Untitled (Tombs) (2016)

Moyra Davey, Untitled (Fire) (2016)

Moyra Davey, Untitled (Daybreak) (2016)

Nandita Raman, Thomas Prinsep Tomb (2016)

Nandita Raman, À la Francesca Woodman (2016)

Moyra Davey, Untitled (Faucets) (2016)