Undated, 1947

I just sit. Or I walk and walk.

Or I stand somewhere looking at one spot. And it seems to me as I stand there that I am totally disconnected from the rest of the world around me. Nothing, absolutely nothing connects me with it.

The world around me goes on being busy, conducts its wars, enslaves countries, kills people, tortures. The real world …

My life till now seems to have slipped through this real world without participating in it, without caring about it, without any connection to it. Even when I was in the very middle of it, I wasn’t really there.

My only life connection is in these scribbles.

Here I stand, this moment, now, with my arms hanging down, the shoulders fallen, eyes on the floor, beginning my life from point zero.

I don’t want to connect myself to this world.

I am searching for another world to which it would be worth connecting myself.

December 7, 1947

Ah, these objects here. I have never seen them.

I have touched them for twenty years. Maybe every day.

But today I am seeing them for the first time.

The hardness. The softness. Colors. Smells.

The room, the table, the chairs, the stove. Everything is here for the first time and I don’t know how to touch tem, how they feel, what they are for.

Potatoes. Bread. Flour.

A cold stream of water on my hands. The coolness of water from the sink on my hands as it runs down my skin.

And the earth.

I step down from the sidewalk and I walk along the strip of the street not covered by concrete. I want to feel the earth under my feet.

Ah. what a feeling, this new feeling of touching the earth, my foot coming in contact with it.

Ah, finally a contact!

I am connecting. I have a connection …

With every step, every movement of my foot I can feel the earth tearing itself away, I have to tear my foot away. With every step I feel how the earth seeps, rises upwards through my body …

Yes, I am part of it. A small fragment of it, but I am a part of it.

I keep walking. I catch myself whistling.

December 11, 1947

Mainz.

No clock in the house where I am sleeping tonight. The woman said she’ll bang on my door at five-thirty. The train leaves at six-thirty. I wake up in the morning—silence everywhere. The church clock is striking four. I fall back into a deep sleep.

I wake up again—it feels like six. I grab my bag and run to the station. Just made the train.

The train crowded all the way.

In Kassel I find Leo. Brought a new issue of Kunstwerk devoted to abstract art. We devour it. Talk until the morning hours.

A new issue of Gintarai. Mazalaitė is attacking the modernists. She says, they don’t suit the Lithuanian spirit. She speaks of course about us. Ah, she is so smart. She knows the Lithuanian spirit like a dead fish. I hope some day we’ll be as smart.

…

December 14, 1947

Adolfas washed out the room. We are all in a very festive mood. A pot full of pea soup is boiling. Got up early—Poškus woke us up. He hauled Leo out, to work on the decor for the Christmas play.

I am reading S. Lewis’s Let Us Play the King.

The weather is mild, but very damp. It’s a warm winter this year. Algis opened the window and shouted, “CHRISTMAS!”

“Don’t say Christmas,” I said, “it doesn’t look like Christmas. Look at the rainy sky. No snow.”

Leo came back. He is sitting now on the edge of this bed with a piece of paper on his knees, a pencil in his hand. Translating Rilke’s Duino Elegies. For a change he has shaved! That is a big event. So he is shining like a young moon. He says, he shaved only because he wants his moustache to stand out: all the girls are crazy about his moustache, he says. That is his opinion.

Adolfas and Algis just completed a game of checkers. Picked up their coats and went out somewhere.

I walk out too. I cross the sports court. Some Germans, all muddy, are playing handball.

I make a circle around the barracks and return. Leo is still working on Rilke. Poškus is visiting, but Leo doesn’t want to talk to him. Poškus is looking through an old issue of Masques, talking mostly to himself, about how idiots and insane asylum inmates are much smarter than any of us. So I walk out again.

December 15, 1947

Snowing badly.

With Leo we traveled to Kassel to hear Beethoven’s First and Ninth symphonies. Came back on foot, late at night through deep soft snow, very excited about the music and the snow.

December 16, 1947

Received log cutter’s certificates.

We are reorganizing our room. We piled up everything in the middle of the room and painted all the walls and the ceiling deep blue. The only kind of paint we could get. We dusted everything off, washed everything, and now the room is neat and clean.

We decided the room now looks a little bit too clean. And too morbid. A little bit like an old -castle tower attic. Leo is climbing all over the beds and books right now, with a pail of paint, writing on the walls, all around the room, a very long incomprehensible sentence—great poetry!—from Heidegger,. The sentence has gone already three times around the room and no end yet in sight.

December 19, 1947

In Mainz I picked up my stipend. Sat through a long lecture on Joyce by a bearded Swiss professor. Took 9 PM train to Frankfurt. Traveled with Prof. Biaggioni, I am taking his course in Italian and Pirandello.

The night ride to Kassel. Luckily, now they have lights in some of the cars, so I can study our magazine treasures. Lancelot. Merkur. In the back issues of Lancelot I read the letters of Romain Roland and L. Masson and the poems of Alain Borne.

My feet are freezing, wet. A lot of wet snow comes into the car at every stop.

From Kassel we walk home on foot, with Algis, through the deep, wet, mushy snow, frozen like dogs. Algis is sick, he is wobbling like a chicken, feverish. But we manage to reach the barracks alive.

December 21, 1947

Collected the weekly food ration. Did laundry.

The snow has melted. Mud and water everywhere. And the wind. Nobody dares to go out. You cross the street—you are wet to the bones. My shoes are full of holes, and they aren’t waterproof. My feet are always wet now.

Leo just came home, from working on the Christmas play, making the sets. He took off his boots and now is warming his wet cold feet in front of the stove. Luckily, we have some coal left.

December 24, 1947

No more rain, but puddles and mud remain.

I am 25.

It is 1 AM, which means, it’s Christmas. Just came back from church.

I am sitting alone in this blue room. The Christmas tree with half-a-dozen candles, a couple of toys strung up.

Ah, to be sitting at a table, Christmas evening, among friends and family … Maybe with a few flowers on the table. The women busy around the stove, excitement … And maybe a cat, and a dog curled under the table, snoozing …

I lived, years ago it seems, I lived at home, surrounded by the people I knew, the world I belonged to. but I neither really knew them nor really saw them. My father, my brothers, my mother, sister. And the house in which I grew up. I lived unconscious of all this. And now, when I feel I am just beginning to live, just beginning to feel that I am alive—that whole other world is gone. Only what memories call back still exists. So I am getting drunk on them.

I am 25 years old so it would seem it’s time to begin to walk more firmly, to live. But it all looks like first steps.

Where is my family, home? Life is so unsure. And what I’ve written till now, it’s all very insignificant. I have to work so much harder than my friends, Leo or Algis. They received a good regular education, they grew up in the cities. My education was fragmentary, always in a hurry. My language—at home we didn’t even speak the written dialect, we spoke a local dialect.

The fourth Christmas away from home. I have no idea, when I sit now in this blue room, if any of my brothers are alive, or my mother, or father. I don’t know if they are sitting now around the table of my childhood.

I do not want to think about it now. And when you forget about it, it looks as if everything is absolutely fine.

But there, at home …

… Evenings before Christmas we used to come home from the sauna, all of us, with red burning faces, clean fresh linen shirts, and we used to sit around the richly set table—and we all ate and drank and sat late, talking and laughing—and we slept on freshly stuffed pillows and mattresses full of fragrant hay. Ah, the smell of dry field flowers …

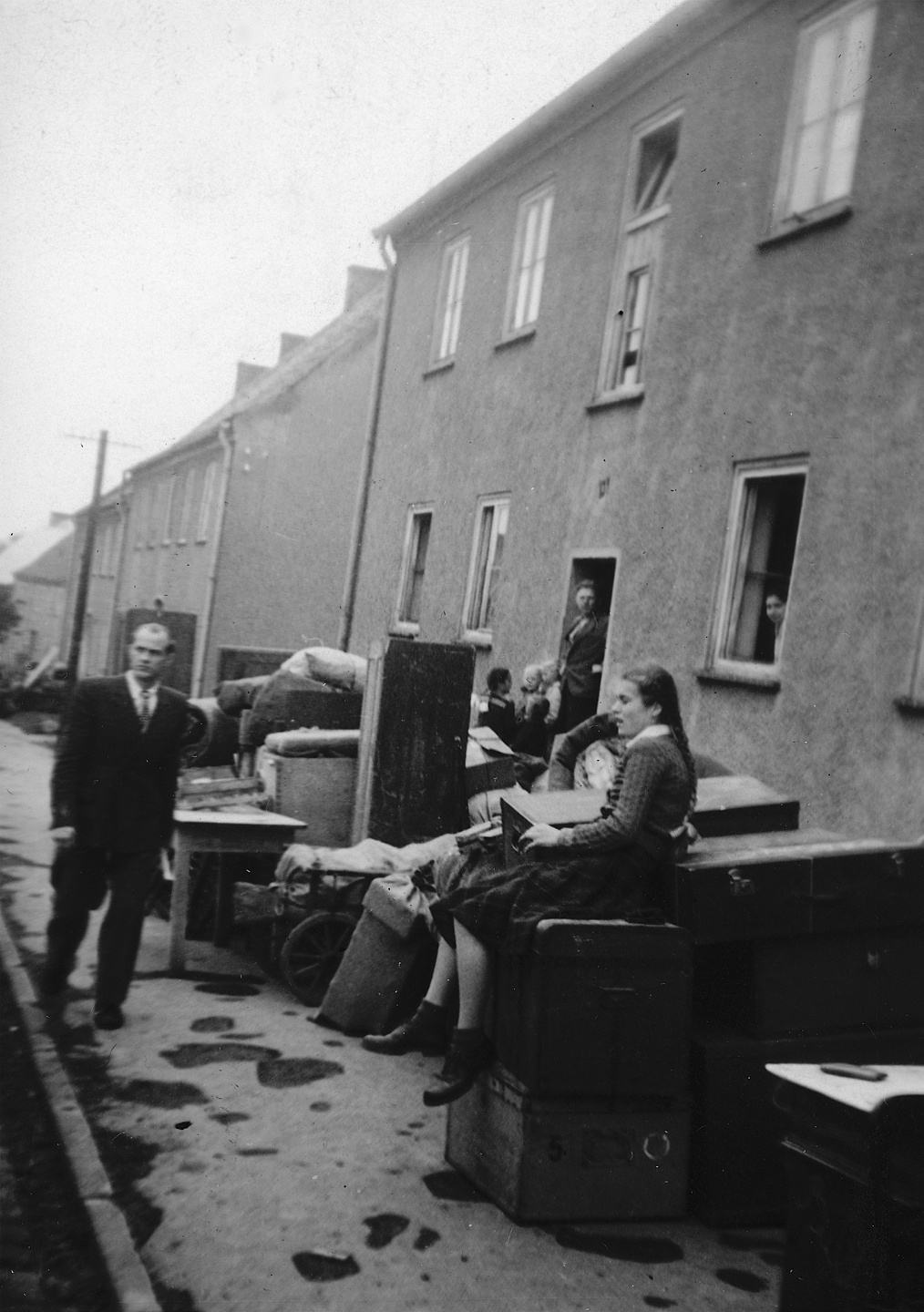

Our good-bye was short. We were never too sentimental, in our family. Our mother left us at our uncle’s house and we stood and looked at her and she stopped just before turning the corner of the house and waved and tears were rolling down her face.

And now it’s Christmas and it’s night. Blue room.

…

January 10, 1948

You are welcome to read all this as fragments, from someone’s life. Or as a letter from a homesick stranger. Or as a novel, pure fiction. Yes, you are welcome to read this as fiction. The subject, the plot that ties up these bits is my life, my growing up. The villain? The villain is the twentieth century.

…

February 2, 1948

Yesterday, in Kassel, I attended a lecture on Buddhism, by a certain Tao Chu. In his soft Chinese voice—he is about sixty, I think—he spoke about differences between East and West, about Leiden (suffering) about the purposelessness of life, and how the arguments and disagreements about the purposelessness of life have produced Faust, and Peer Gynt, and the whole Western thought which looks very silly to the Easterners … The West, he said, is almost identical with Denkakt, the act of thinking, reason. He spoke about Ich, I, Me, which a child only around the fourth year begins to be aware of—the second birth. He also said, that the only times that we really deeply experience joy, sadness and beauty, is when we do not think of it. Denkakt kann nicht(s) geniessen. (Thinking can experience/enjoy nothing.)

Antaeus … Unbeatable as long as he held to Mother Earth which filled him with life and strength. Yes, Mother Earth, now cut off from under me. How long can I hold out, uprooted?